Sean Dillon is a Pākeha male – but he’s in the minority.

He is a school teacher – a field where three-quarters of the population are female.

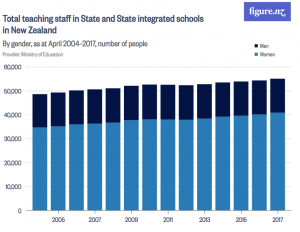

New Zealand has 55,020 registered teachers, as at April 2017 – 40,819 of these are women. That is almost three times the 14,201 male teachers educating our children.

Dillon, who works at Welbourn School in New Plymouth, says teaching doesn’t have the aura of some other male-dominated fields.

“The perception of the job is not like a high-flying career…It doesn’t have the aura of a big bank or investor. It depends what you’re after in a career. Pay would help, and public perception.

“It needs to be a more attractive profession in general.

“In New Zealand there’s the workload requirements that can sometimes get a little bit out of balance.

“For me, my fears in the future are providing for my family and things like that.”

Most primary teachers with a bachelor’s degree would start at an annual pay level of about $47,980, which over the years can get as high as $75,949. But that’s where the base salary stops.

Most primary teachers with a bachelor’s degree would start at an annual pay level of about $47,980, which over the years can get as high as $75,949. But that’s where the base salary stops.

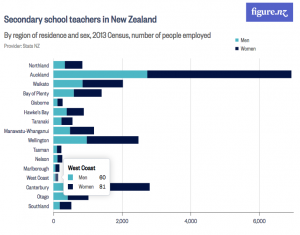

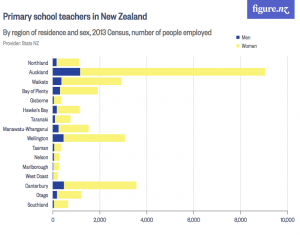

Ministry of Education figures show 12 per cent of primary school teachers are male, compared to 40 percent of high school teachers. In ten years, the overall percentage has not changed much – 71.6 per cent of teachers were female in 2004.

Sam Knox is one of three males in a staff of 40 at Marfell School. He says that when he tells people his job he occasionally gets looked down on, but most people, while surprised that he teaches primary age children, are supportive.

“I think there’s mana in the right circles.”

He says it’s important for kids to have positive role models, both male and female – especially if they don’t have it at home. Male teachers can pass on psychological lessons, including respecting women.

“I’ve got lots of females above me in authority and being respectful to them and the females around me – the kids see ‘If Mr Knox does that I can do that. I can be respectful to the females around me’. And sometimes that’s not the truth in home life, unfortunately.

“I honestly think that we tick a bit different…how we process things. It’s good for the children to get both sides.”

He sees two reasons why men are hesitant to become involved in education – he says men in the sector need to be celebrated more, and there is also the anxiety of being accused of inappropriate or harmful behaviour.

“That’s a big fear that people have, that someone will say something and their life is ruined.

“Take away the stigma that accusations are going to be flying left, right and centre.”

Those changes in perception and stigma could see men more likely to consider education as a career.

Those changes in perception and stigma could see men more likely to consider education as a career.

Dr Alison Sewell, associate professor at Massey University’s Institute of Education and leader of the Masters in teaching and learning, says more males are coming into the profession, and into her class, but the undercurrent of vulnerability remains.

In 1993, Canterbury teacher Peter Ellis was convicted of 16 sexual offences relating to his time at Christchurch Civic Creche and sentenced to 10 years in jail. The case turned into a witch hunt. He still maintains his innocence, and has made several legal appeals and political bids to overturn the convictions over the years.

Sewell says the case, as well as others, has left a mark.

“There’s also probably a bit of a fear of the Peter Ellis case – ‘I don’t want to make myself vulnerable in a classroom’. We talk about that and put the fears out on the table.”

One of her student teachers had an incident with a couple of high school girls, she said.

“A couple of girls made up a story about something that had happened, that hadn’t happened, but it was an attention-seeking thing. It traumatised this poor male student teacher.”

And it can do worse than emotional trauma – teacher suspensions and disciplinary tribunals happen regularly, and while some are deserved, not all are.

But that fear should not be a barrier, Sewell says, with all the support systems now in place if a male teacher is falsely accused. It is something they discuss regularly at her class.

“Always make sure the door is open; always make sure you report what’s just happened if you think there’s a sniff of anything; the whole touching thing – it’s OK to touch someone on the shoulder if they’re crying on the playground.”

Male role models in the classroom are crucial, she says, especially with a lot of kids growing up in difficult circumstances. Even in the six-hour school day, they have a lot of influence.

“That’s a really powerful way to get a child when they’re five.”

“That’s a really powerful way to get a child when they’re five.”

But diversity is only one facet of the equation – not the be-all and end-all.

President of the teacher’s union NZEI Te Riu Roa, Lynda Stuart, says diversity is no good if it’s just for the sake of diversity.

“It’s absolutely important first and foremost that we have good teachers, whether the good teachers are male or whether they’re female.

“There is definitely not enough gender diversity in the profession, and a lot of the pay and workload issues we are currently campaigning against are part of the problem.”

Principal of Sacred Heart Girls’ College, Paula Wells, has seven males out of 52 teaching staff, and says while a better gender balance would be good, her priority is the best person for the job.

“It would be great to have more male teachers in our environment. If a male were the best candidate for any advertised vacancy, and a great fit for our culture and values, I would employ them.”

The strong female dominance in the profession was partly due to “antiquated stereotypes”, she says.

“Teaching, along with nursing, was a vocation strongly encouraged of female school-leavers seeking further education in years gone by.

“It has also been seen, rather stereotypically by earlier generations, as a profession that worked well for women, in that they could continue to be a primary caregiver for their own children and hold down a teaching job, with the ‘luxury’ of school hours and school holidays.”

But for Dillon, teaching has given him opportunities to travel, teaching in Peru and Brunei. He first got into the profession after seeing how enthusiastic his flatmate was about her job.

The profession clearly has its challenges, including pay and workload, but a lot depends on the work environment, he says.

“The most enjoyable for me is when I’m in the classroom, we’re progressing through a unit of work and I’m seeing real learning happening.

“I don’t think people should shy away from it.

“There is a certain joy that you can bring to kids’ lives and it is a really, really special and important part.

“You get parents saying I’m so thankful that my son or daughter’s had a male teacher.”