Mr. Mike’s Legacy

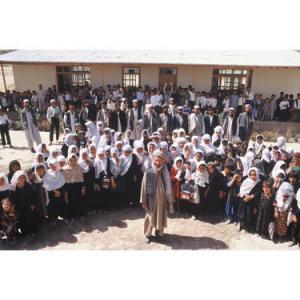

The school that Mike Frastacky built has seven sturdy buildings with galvanized steel roofs and precise orange framing, surrounded by the barren mountains of northern Afghanistan’s Baghlan province.

The children laughing in the playground walk here each morning from 10 villages. Enrolment is almost 700, depending on whether the rivers are swollen or the wheat and rice needs harvesting. More than half of the students are girls.

“Please stand up,” a young male teacher says as he enters a classroom where 20 Grade 7 girls sit cross-legged on pale blue Afghan carpets, awaiting English class, their pens and UNICEF notebooks ready. The girls stand in unison. “How are you?” the teacher asks.

“Very good,” the girls respond before sitting to begin lessons.

Anyone who thinks Canadians are not making a difference in Afghanistan, that all they are doing is fighting Taliban while trying to dodge roadside bombs, has probably never heard of the Maktab Hazrat Osman School.

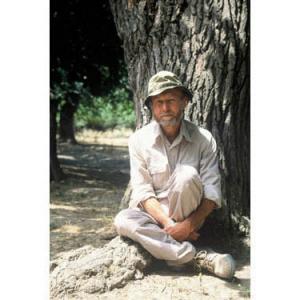

It was built by Mr. Frastacky, a Vancouver carpenter who constructed it from scratch using the skills of his trade and money he contributed himself and collected from friends. He spent US$80,000 on the project. It also cost him his life.

It was built by Mr. Frastacky, a Vancouver carpenter who constructed it from scratch using the skills of his trade and money he contributed himself and collected from friends. He spent US$80,000 on the project. It also cost him his life.

A year ago, on July 23, two gunmen awoke the 56-year-old humanitarian in the night and shot him three times in the chest. Police have concluded it was a political killing, ordered by the insurgent group Hezb-e Islami. Schools mean a return to normalcy, and insurgents thrive on chaos.

Afghanistan is now Canada’s biggest development program. The school at Nahrin is only one small project, but it is a symbol of both the successes achieved by Canadians and the challenges they face in a country that needs everything but where resistance to change and to outsiders is rooted in deeply conservative traditions and foreign-backed Islamist groups.

While critics say Canada is not doing enough development work in Afghanistan, Mr. Frastacky’s murder points to a more subtle reality: that Canada is improving the daily lives of Afghans, but there are consequences to pushing too hard, too fast for change–and they can be fatal.

While critics say Canada is not doing enough development work in Afghanistan, Mr. Frastacky’s murder points to a more subtle reality: that Canada is improving the daily lives of Afghans, but there are consequences to pushing too hard, too fast for change–and they can be fatal.

“I was shocked, horrified when I heard that Mike was killed,” said Gary Moorehead of Shelter for Life, a charity that rebuilt homes in the area following a 2002 earthquake that killed more than 1,000 and left thousands homeless. “Lots of people were ashamed that Mike Frastacky was killed. But you know, maybe he expected too much from the Afghan people.”

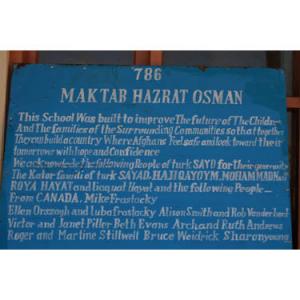

A plaque mounted inside the school reads: “This school was built to improve the future of the children and the families of the surrounding communities so that together they can build a country where Afghans feel safe and look toward their tomorrows with hope and confidence.”

It is a fitting–if unexpected–epitaph to the man whose legacy this became.

The Frastacky family immigrated to Canada following the Second World War. Rudolph Frastacky was an anti-communist politician in Bratislava, and when the communists began to take control of Slovakia, he fled to Switzerland. He procured fake French passports so his wife, daughter Luba, son Fedor and aunt could get to the American-controlled zone in Austria. They went to Switzerland, Italy, France and, finally, Canada. Mike Frastacky was born a year later.

The Frastackys had career ambitions for their youngest son, but he had his own ideas. He wanted to work with wood. In the early 1970s, he left Toronto and moved to Vancouver to apprentice with a marine carpenter.

He loved to travel and visited 50 countries, often choosing remote locations such as the Western Sahara, Yemen and Madagascar. He was particularly taken by the mountains that hug the borders of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan. He felt at peace there, he would tell friends at the slide shows he gave when he returned home. “Mike fell in love with the Afghan people and wanted to do something for them,” his sister Luba said.

He loved to travel and visited 50 countries, often choosing remote locations such as the Western Sahara, Yemen and Madagascar. He was particularly taken by the mountains that hug the borders of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan. He felt at peace there, he would tell friends at the slide shows he gave when he returned home. “Mike fell in love with the Afghan people and wanted to do something for them,” his sister Luba said.

Rather than joining an aid organization, he decided to go it alone. Together with a California businessman of Afghani origin named Hamayoun Kator, Mr. Frastacky put together blueprints for a school.

“Mike wanted 20% of the money for the school to come from the local people. But the local people did not have this much money,” said Mr. Kator. “I promised to him, I will collect this money from my family and I give to him to build the school.”

The school grounds are off a remote dirt road outside the village of Turk Sayad. Mr. Frastacky lived nearby at Mr. Kator’s Western-style bungalow. It had a rose garden and peach and apricot trees, surrounded by a high fence. One of Mr. Kator’s nephews, Liaqat Hayat, worked as his interpreter.

Mr. Hayat and Mr. Frastacky first worked together in 2002, when Mr. Frastacky was looking into renovating an orphanage in Faizabad, in the northern province of Badakshan. They became close friends, travelling together while the Canadian searched for a project.

He found it in the village of Turk Sayad. “There are ruined mud brick villages everywhere and most people have been living in military-type tents for the last year,” he wrote in an e-mail.

The locals welcomed his plans to build a permanent school. Many schools in Afghanistan are simple white UNICEF tents with nothing to keep out the cold in winter or the sand during the scorching summers.

He hired local tradesmen to help with construction. Rather than using traditional Afghan building methods, he insisted on a more sturdy design in line with his high standards. He built classrooms, a well and a library stocked with books. He organized teachers’ seminars, and an adult women’s education class.

Mr. Frastacky sometimes butted heads with the Afghans. He did not get along with Nahrin’s top education official; he considered him corrupt, describing him in e-mails as a “cretin” and opium kingpin. He fumed at the village that would only allow its children to attend the school up to Grade 4, and called it “barbaric” when a father threatened a family with a Kalashnikov when it declined to marry off their 15-year old daughter to his son.

Mr. Frastacky sometimes butted heads with the Afghans. He did not get along with Nahrin’s top education official; he considered him corrupt, describing him in e-mails as a “cretin” and opium kingpin. He fumed at the village that would only allow its children to attend the school up to Grade 4, and called it “barbaric” when a father threatened a family with a Kalashnikov when it declined to marry off their 15-year old daughter to his son.

His frustrations always met the same response: That’s just the way things are done here.

“You have to remember, we are foreigners in their country,” said Klaus Bar, a German aid worker with Op Mercy Afghanistan. “You can’t take your European or North American yardstick or way of thinking and expect Afghans to think the same way. You just can’t do that.”

Between trips to Nahrin, Mr. Frastacky worked in Vancouver as a self-employed cabinetmaker and high-end finishing carpenter. He drove a van to his contract jobs and also owned a Miata that he loaned to friends when he was away. He sold his duplex in a leafy residential district of Vancouver’s west side and had just bought a dream house he hoped to spend months renovating.

He returned to Afghanistan every year for months at a time.

“Why do it?” he once wrote. “What are the positives? ?It has come down to wanting to create an opportunity for a group of kids to seek their potential and be supported in their aspirations.

“It has not been an easy job,” he wrote another time. “I have had to deal with corruption, lies, arrogance and laziness. I was hoping that after this visit, I could step back from the school and leave the daily operation of it to the headmaster and teachers and to you, the parents of the students.”

“It has not been an easy job,” he wrote another time. “I have had to deal with corruption, lies, arrogance and laziness. I was hoping that after this visit, I could step back from the school and leave the daily operation of it to the headmaster and teachers and to you, the parents of the students.”

Instead, he complained of laziness among many staff at the school, the custodian not cleaning, sports equipment being stolen and a problematic headmaster he had to fire.

A new headmaster is in charge and the 20 male teachers cover subjects ranging from math, science, English, history, and geography to Pashto, Dari, Arabic, the Koran, poetry and physical education. Last year, the school offered grades 1 to 6. This year Grade 7 was added. Mr. Frastacky intended to add another grade every year up to Grade 9.

In one classroom, the teacher writes on the blackboard: A B C D E F G and asks the girls to repeat the letters. One of the girls says she wants to become a doctor. Another wants to be teacher. One says she wants to be president of Afghanistan.

In one classroom, the teacher writes on the blackboard: A B C D E F G and asks the girls to repeat the letters. One of the girls says she wants to become a doctor. Another wants to be teacher. One says she wants to be president of Afghanistan.

“All of Nahrin knew and loved Mr. Mike,” said Abdul Qadir, who runs the local pharmacy. “I asked him, ‘Do you have any children?’ He said, ‘Yes, I have 600 children going to my school.’ I thought to myself, ‘What a good man and God bless him.”

Friends say Mr. Frastacky felt safe in Afghanistan because of the goodwill he had earned with his school. “He felt protected,” said his friend Shelley Hall. “However, towards the end, Mike was feeling more and more worried about the situation in Nahrin.”

Baghlan province was descending into lawlessness when Mr. Frastacky returned last year. Programs to disarm militant groups had been poorly implemented and the province remained awash with weapons. Warlords were growing illegal poppy crops and committing crimes with impunity. Police were unprofessional, untrained and maintained close ties to the warlords, gangs and insurgent groups.

Mr. Kator and Mr. Hayat advised Mr. Frastacky against returning to the school. “I met him at his hotel in Kabul and I told him that the criminal and political situation in Nahrin was very bad,” Mr. Kator recalled. “I begged him not to go. But Mike was so headstrong, I could not stop him.”

Mr. Frastacky was aware of the risks. The e-mails he sent shortly before his death hinted at his concern over the disintegrating security: “I have still not armed myself, though if the opportunity presented itself I would not hesitate. I am looking into ‘renting’ a Kalashnikov while I am here but no one seems to want to part with theirs for some reason ? I am fairly convinced that my connection with the school offers me–and I use this word loosely — some protection.”

One day, he drove past the scene of a suicide bombing that had occurred an hour earlier. “The government just can’t seem to get anything better than a tenuous hold on the security situation and it seems frightened to assert itself for fear of upsetting the populace,” he wrote. But he was reassured that NATO troops seemed to be moving into the region. He wrote to his sister saying he would return to Canada by August.

“Mike would never want to be remembered as a martyr,” said his friend Ms. Hall. “He loved that part of the world and wanted to help the Afghan people. Mike was a complex man who lived life to the fullest.”

“Mike would never want to be remembered as a martyr,” said his friend Ms. Hall. “He loved that part of the world and wanted to help the Afghan people. Mike was a complex man who lived life to the fullest.”

The night of the murder, it was hot and muggy in Nahrin. Mr. Hayat was sleeping on a mattress in the front garden under a canopy.

“At around 1 a.m.,” he recalls, “two tall and thin men wearing black turbans and white shalwar kameez [cotton tunic and pants] woke me up by savagely beating me with the back of their Kalashnikovs.”

They tied his hands and forced their way into the house, dragging him with them to the room where Mr. Frastacky was sleeping.

The guard, Muhammad Nawab, was asleep outside his room. He tried to shoot the gunmen but his gun jammed. He ran outside to get help.

“The two killers pulled Mike into the bathroom, then shut the door, but they left me right outside,” Mr. Hayat said. “I heard one shot, then the second shot, followed by the third. I started to cry as I knew they had killed him.”

The neighbours arrived and opened fire at the men but they got away. Locals reported seeing 10 other men. Police arrived an hour later. Mr. Hayat told them he was unable to see the killers’ faces since they wore scarves. “But with their black headscarves they could have been Taliban men or some other group.”

He thinks their original plan was to kidnap Mr. Frastacky, but they shot him dead when they met resistance. An investigation by the Afghan Ministry of Interior concluded anti-government groups planned the murder, most likely Hezb-e Islami.

Police took Mr. Hayat, the bodyguard and two neighbours into custody and held them for almost two months. Four other men who Afghan intelligence sources claim belonged to “a gang of killers and looters” were later arrested, but locals said they have since been released as well.

I don’t know who it was who killed Mike,” Mr. Kator said. “It might be robbers, might be government, might be police. There are a lot of people here who are uneducated people. And they don’t like the education.”

The Canadian Ambassador to Afghanistan, Arif Lalani, said he had seen the police reports and the file on the case but could not comment further.

“His story is a tragic one and a very unfortunate one,” he said. “There are security precautions that I think aid workers and other Canadians who are working here take and that’s part of doing business here.”

Metal posts encircle the school, the foundations of the wall that Mr. Frastacky was building to keep the donkeys, goats and sheep out of the playground and the classrooms.

Mr. Kator has vowed to finish the wall.

Mr. Frastacky’s dog still wanders around, well fed by the locals. His name is Lucky.

The villagers all remember “Mr. Mike” and what he did for their children, but few Canadians know this place or realize that Canada’s official death count in Afghanistan is 66 soldiers, one diplomat and a carpenter.