From pre-kindergarten through high school, Omar Marquez only had one teacher who looked like him. Now that he’s an educator himself, Marquez knows he’s one of the only Hispanic male teachers many students at his school will ever see. Marquez is a restorative practices coach at Applied Learning Academy, a middle school in the Rosemont neighborhood. It’s a role he transitioned into this year after teaching sixth-grade science at the school for two and a half years. As a Latino, Marquez knows many of the students at the school see him as a reflection of their own backgrounds. Most years, close to half of the students at the school are Hispanic, state records show, while about three-quarters of the teachers are white.

The representation he provides is important, Marquez said, because kids learn about how the world works by watching what goes on around them. If they don’t see people who share their backgrounds in roles that they aspire to, he said, they’re less likely to think those jobs are available to them. “Having those role models that look like you is huge. It’s huge,” he said.

Like many school districts across Texas and nationwide, Fort Worth ISD has a pronounced demographic mismatch between its teachers and its students. District leaders say they’re stepping up efforts to recruit more teachers who reflect the student body. But education researchers say it isn’t enough to focus only on recruiting those teachers — district leaders must also support those new educators so they don’t leave the classroom after only a few years.

Like many school districts across Texas and nationwide, Fort Worth ISD has a pronounced demographic mismatch between its teachers and its students. District leaders say they’re stepping up efforts to recruit more teachers who reflect the student body. But education researchers say it isn’t enough to focus only on recruiting those teachers — district leaders must also support those new educators so they don’t leave the classroom after only a few years.

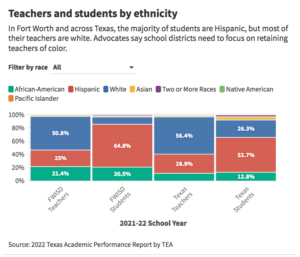

In Fort Worth and across Texas, teacher workforce is whiter than schools Most years, nearly two-thirds of students in Fort Worth ISD are Hispanic, but Hispanic teachers make up only about a quarter of the district’s workforce, state records show. Meanwhile, about half the teachers in the district are white, while white students make up the district’s third largest ethnic group, most years about 10-12% of the district’s student body.

Fort Worth ISD isn’t the only Tarrant County district where that mismatch exists. In Arlington ISD, about 57% of the district’s teachers during the 2021-22 school year were white, state records show. But white students made up the third-largest ethnic group in the district, with just 17%. Meanwhile, about 21% of the district’s teachers were Hispanic, but Hispanic students made up about 48% of the district’s enrollment. A similar mismatch exists statewide, although it isn’t as wide as the one in Fort Worth ISD.  Across Texas, about 53% of students enrolled in public schools during the 2021-22 school year were Hispanic, state records show. But only about 29% of the state’s teachers were Hispanic. White teachers made up 56% of the state’s educator workforce, but only about 26% of students were white. Notably, both in Fort Worth ISD and statewide, the percentage of Black teachers was relatively closely aligned with the percentage of Black students. Mia Hall, the Fort Worth district’s executive director of equity and community collaborations, said district leaders are stepping up efforts to recruit teachers of color, especially men. District leaders are mainly focusing on building partnerships with Hispanic-serving institutions and historically Black colleges and universities, she said. As they build those relationships, recruiters can’t focus only on colleges of education, Hall said. New educators who come into the profession straight out of a four-year teacher college make up a small percentage of the state’s first-year teachers. A much larger percentage come through alternative certification programs, pathways into the classroom for career changers. That means recruiters need to target students who are majoring in something other than education, as well as those who haven’t decided what they want to do after college, she said. A’Myiah Maurice, 10, follows along with her teacher Kristi Jones, a fourth-grade reading and language art teacher, as she reads ‘Treasure Island’ to her class at South Hi Mount Elementary in Fort Worth on Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2023.

Across Texas, about 53% of students enrolled in public schools during the 2021-22 school year were Hispanic, state records show. But only about 29% of the state’s teachers were Hispanic. White teachers made up 56% of the state’s educator workforce, but only about 26% of students were white. Notably, both in Fort Worth ISD and statewide, the percentage of Black teachers was relatively closely aligned with the percentage of Black students. Mia Hall, the Fort Worth district’s executive director of equity and community collaborations, said district leaders are stepping up efforts to recruit teachers of color, especially men. District leaders are mainly focusing on building partnerships with Hispanic-serving institutions and historically Black colleges and universities, she said. As they build those relationships, recruiters can’t focus only on colleges of education, Hall said. New educators who come into the profession straight out of a four-year teacher college make up a small percentage of the state’s first-year teachers. A much larger percentage come through alternative certification programs, pathways into the classroom for career changers. That means recruiters need to target students who are majoring in something other than education, as well as those who haven’t decided what they want to do after college, she said. A’Myiah Maurice, 10, follows along with her teacher Kristi Jones, a fourth-grade reading and language art teacher, as she reads ‘Treasure Island’ to her class at South Hi Mount Elementary in Fort Worth on Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2023.

The district is also continuing to work with staff members like paraprofessionals, classroom aides and substitute teachers to get them certified to teach, Hall said. Many school districts across the state, including Fort Worth ISD, have launched so-called grow your own programs as a way of combating post-pandemic teacher shortages. Hall said those programs can also be a good way for districts to recruit teaching candidates from underrepresented groups. “There are people sitting in our classrooms or on our campuses who would make great teachers, who would make great counselors, administrators and, ultimately, superintendents,” she said. Similar backgrounds can help with relationships Relationship building is a key part of the work Marquez does as a restorative practices coach. When a student gets in  trouble, it’s his job to help them understand where they went wrong and try to repair the damage. That work takes trust on both sides, he said. The fact that Marquez shares a background with many of the students at his school makes it quite a bit easier to build the personal connections that can serve as the starting point for that trust, he said. The connection points don’t need to be anything too weighty, he said — middle schoolers love to talk about snack food preferences, he said, so a conversation about favorite flavors of Takis or types of Mexican candy can be as good a place to start as any. The key thing is to be authentic, he said. “Middle schoolers, they can smell the BS,” he said. “They can tell when someone is faking interest or they can tell whenever you’re trying to be phony with them.” Marquez said he’s noticed that Hispanic teachers tend to become unofficial translators for their campuses, which takes time away from the already-heavy workload they have as teachers. If the district wants to do a better job of retaining those bilingual teachers, Marquez says, they ought to offer an extra stipend in recognition of the work they do as translators for other teachers.

trouble, it’s his job to help them understand where they went wrong and try to repair the damage. That work takes trust on both sides, he said. The fact that Marquez shares a background with many of the students at his school makes it quite a bit easier to build the personal connections that can serve as the starting point for that trust, he said. The connection points don’t need to be anything too weighty, he said — middle schoolers love to talk about snack food preferences, he said, so a conversation about favorite flavors of Takis or types of Mexican candy can be as good a place to start as any. The key thing is to be authentic, he said. “Middle schoolers, they can smell the BS,” he said. “They can tell when someone is faking interest or they can tell whenever you’re trying to be phony with them.” Marquez said he’s noticed that Hispanic teachers tend to become unofficial translators for their campuses, which takes time away from the already-heavy workload they have as teachers. If the district wants to do a better job of retaining those bilingual teachers, Marquez says, they ought to offer an extra stipend in recognition of the work they do as translators for other teachers.

Teachers of color often find themselves isolated, researcher says Aside from serving as translators, male teachers of color also tend to be asked to handle all the discipline issues on their campuses, said Constance Lindsay, a professor in the College of Education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. That’s especially true if they’re the only male teachers of color on their campuses, she said. Like translating duties, those discipline issues take time away from teachers’ other work and interfere with efforts to develop their instructional skills, she said. Finding a solution to that issue can be tricky, Lindsay said, because decisions about where teachers are placed are often made by more than one person. In some districts, hiring managers might have the final word on who teaches where, but principals often also have a great deal of input into who works in their buildings. If district officials want to make sure their teachers feel supported, they should start by making sure they don’t feel like they’ve been placed on an island — “having one of anything is probably not the best way to do it,” she said. One of the key challenges that has frustrated efforts to place more teachers of color in classrooms across the country is the fact that there are leaks at every step of the teacher pipeline, Lindsay said. Black and Hispanic students are less likely to enroll in college than their white peers, she said, and those who do go to college are less likely to major in education. With the exception of Black- and Hispanic-serving schools, colleges of education tend to be whiter than the student bodies of the universities that house them, she said. First-grade teacher Luis Ortiz goes over vowels with his class at South Hi Mount Elementary in Fort Worth on Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2023.

Once they leave college and enter the workforce, teachers of color are also more likely to leave the profession than their white counterparts, she said. That could be at least in part because teachers of color are more likely to work in high-need and hard-to-staff campuses, she said. “A lot of times they’re getting into the work because they want to work in those types of schools, but we need to consider that they may be burned out,” she said. All those factors combined add up to a self-reinforcing problem: Researchers say that Black and Hispanic students are less likely to earn a college degree if they don’t have teachers who reflect their backgrounds. But if colleges don’t graduate enough teaching candidates of color, school districts can’t recruit enough Black and Hispanic teachers who can act as role models for their students. “We’re kind of in this vicious cycle,” Lindsay said. First-grade teacher Luis Ortiz goes over vowels with his students during class at South Hi Mount Elementary in Fort Worth on Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2023.

Once they leave college and enter the workforce, teachers of color are also more likely to leave the profession than their white counterparts, she said. That could be at least in part because teachers of color are more likely to work in high-need and hard-to-staff campuses, she said. “A lot of times they’re getting into the work because they want to work in those types of schools, but we need to consider that they may be burned out,” she said. All those factors combined add up to a self-reinforcing problem: Researchers say that Black and Hispanic students are less likely to earn a college degree if they don’t have teachers who reflect their backgrounds. But if colleges don’t graduate enough teaching candidates of color, school districts can’t recruit enough Black and Hispanic teachers who can act as role models for their students. “We’re kind of in this vicious cycle,” Lindsay said. First-grade teacher Luis Ortiz goes over vowels with his students during class at South Hi Mount Elementary in Fort Worth on Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2023.

The shortage of teachers overall has forced school districts to find creative ways of breaking that cycle, Lindsay said. Many districts, struggling to find enough teachers to staff their classrooms, have started working with non-certified staff members like paraprofessionals and classroom aides to get them certified to teach, she said. While those programs don’t generally target teachers of color specifically, they offer opportunities to staff members who likely wouldn’t have had them otherwise. By working with existing employees, districts are investing in candidates who have already shown an interest in working in classrooms, which Lindsay said makes them more likely to stay on after getting certified to teach. Keeping teachers of color is as important as recruiting, advocate says Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, said many school districts across the country have contacted his organization to talk about how to recruit more teachers of color. But in most cases, he said, those districts don’t have a plan to retain the teachers of color they already have. The first step in keeping teachers of color is making sure their perspectives and experiences are valued, El-Mekki said. Many school district leaders have a remarkable lack of understanding or curiosity about what it’s like to be a person of color working in the American education system, he said. If district leaders aren’t serious about understanding those teachers’ experiences, it will be all the harder for them to retain them, he said. School leaders often have a misconception that racism doesn’t exist inside schools, El-Mekki said, even if they acknowledge the ways it affects society more broadly. But that isn’t the case, he said. Schools are microcosms of society, so whatever problems exist outside their walls will affect them, as well, he said. At the worst, El-Mekki said, teachers of color can find themselves in a position where they’re dealing with three challenges at once: When teachers of color are on the receiving end of racial bias from coworkers and colleagues, it causes problems for them in the moment. But it can also dredge up unprocessed trauma from things they experienced earlier in life, he said. Even as those teachers are dealing with those dueling challenges, they often feel as though they have to advocate for students in their schools who look like them, so they don’t go through the same struggles, he said.

Compounding those challenges further is the fact that many teachers of color, especially men, work in buildings where no one shares their background, El-Mekki said. So they often feel as though they have no one to confide in, he said. “All of these things create what can be this toxic culture for an educator of color,” he said. Black teacher pipeline never recovered after desegregation El-Mekki said the Black teacher pipeline has never recovered from the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, the landmark 1954  U.S. Supreme Court ruling that struck down school segregation laws across the country. Although the decision was hailed as a civil rights victory, it also meant the end of a school system where Black students were taught primarily by teachers who shared their backgrounds. After desegregation, school districts were, at least in some cases, willing to accept Black students at white schools, El-Mekki said, but even the most effective teachers who had worked in Black schools for years largely lost their jobs. Fort Worth ISD began implementing various efforts to integrate schools in 1963, such as a “stair step” integration plan in which one grade would be desegregated every year, busing and the closure of some schools, such as I.M. Terrell High School, Como Junior and Senior High School, Kirkpatrick High School and several elementary schools. But many of the families the process was meant to benefit say the way it was handled caused harm. Robert Glenn, a former Fort Worth ISD student, said the process hurt a lot of people including students, teachers and communities, as it didn’t give people the path that they needed to be successful. Glenn, who is Black, grew up in the Como neighborhood and attended Como Middle

U.S. Supreme Court ruling that struck down school segregation laws across the country. Although the decision was hailed as a civil rights victory, it also meant the end of a school system where Black students were taught primarily by teachers who shared their backgrounds. After desegregation, school districts were, at least in some cases, willing to accept Black students at white schools, El-Mekki said, but even the most effective teachers who had worked in Black schools for years largely lost their jobs. Fort Worth ISD began implementing various efforts to integrate schools in 1963, such as a “stair step” integration plan in which one grade would be desegregated every year, busing and the closure of some schools, such as I.M. Terrell High School, Como Junior and Senior High School, Kirkpatrick High School and several elementary schools. But many of the families the process was meant to benefit say the way it was handled caused harm. Robert Glenn, a former Fort Worth ISD student, said the process hurt a lot of people including students, teachers and communities, as it didn’t give people the path that they needed to be successful. Glenn, who is Black, grew up in the Como neighborhood and attended Como Middle  School, but had to be bused to the then-majority-white Arlington Heights High School when the district closed Como High School in the early 1970s. Seeking more football playing time, he transferred to Western Hills High School, where he graduated in 1977. Through elementary and middle school, Glenn had Black teachers who lived in the same community, went to church with his parents, understood their backgrounds, and thus cared about his success. During his four years of high school, he navigated through race issues, as opposed to being there to learn, he said. His teachers knew little about the incoming Black students, and many white students were raised to resent their new Black classmates, he said. “When the Black kids were being bused to Western Hills the white kids always felt like we were being put into their environment,” Glenn said. “And that they were losing something, versus the other way around.” Schools are supposed to enhance communities, Glenn said, providing parent and teacher interactions and even holding events for the community. As schools were shut down in communities and kids were bused around the area, parents couldn’t visit their kids’ schools as easily because they were too far away, he said. That distance caused a lack of communication and close relationships which many families were used to, he said. ‘Foundational trust’ is key for student relationships Marquez, at Applied Learning Academy, is one of several Hispanic teachers and support staff at the campus, and some of the teachers who are now his coworkers were already working on campus when he was there as a student. So he hasn’t had the experience of being the only Hispanic male teacher at his school, he said. That’s been helpful, he said — teachers who are the only ones from their backgrounds on their campuses can feel isolated and unable to connect with their colleagues. Marquez said it’s crucial that the district supports the teachers of color it already has and works to foster an environment in which future educators will want to come work. Ultimately, in doing so, the district will be supporting its students, he said. “We want the students to be able to come to adults when things get hard or when they’re facing something difficult,” Marquez said. “But if they don’t have that foundational trust, then that becomes hard for them.”

School, but had to be bused to the then-majority-white Arlington Heights High School when the district closed Como High School in the early 1970s. Seeking more football playing time, he transferred to Western Hills High School, where he graduated in 1977. Through elementary and middle school, Glenn had Black teachers who lived in the same community, went to church with his parents, understood their backgrounds, and thus cared about his success. During his four years of high school, he navigated through race issues, as opposed to being there to learn, he said. His teachers knew little about the incoming Black students, and many white students were raised to resent their new Black classmates, he said. “When the Black kids were being bused to Western Hills the white kids always felt like we were being put into their environment,” Glenn said. “And that they were losing something, versus the other way around.” Schools are supposed to enhance communities, Glenn said, providing parent and teacher interactions and even holding events for the community. As schools were shut down in communities and kids were bused around the area, parents couldn’t visit their kids’ schools as easily because they were too far away, he said. That distance caused a lack of communication and close relationships which many families were used to, he said. ‘Foundational trust’ is key for student relationships Marquez, at Applied Learning Academy, is one of several Hispanic teachers and support staff at the campus, and some of the teachers who are now his coworkers were already working on campus when he was there as a student. So he hasn’t had the experience of being the only Hispanic male teacher at his school, he said. That’s been helpful, he said — teachers who are the only ones from their backgrounds on their campuses can feel isolated and unable to connect with their colleagues. Marquez said it’s crucial that the district supports the teachers of color it already has and works to foster an environment in which future educators will want to come work. Ultimately, in doing so, the district will be supporting its students, he said. “We want the students to be able to come to adults when things get hard or when they’re facing something difficult,” Marquez said. “But if they don’t have that foundational trust, then that becomes hard for them.”

December 08, 2023