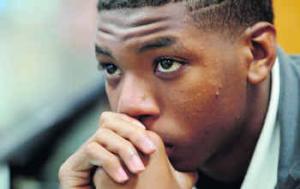

A group of teenage boys dressed in formal attire form a circle and join hands inside a classroom on a recent evening inside Dallas’ Carter High School.

One by one, they’re asked to contribute a positive affirmation. Don’t be a follower. Life is full of choices. Control your anger.

Lastly, they speak in unison: “Man Up.” They’re in a mentoring program by the same name launched by art teacher Curtis Ferguson that aims to improve the performance of young black male students.

An increasing number of advocacy organizations nationwide are examining the achievement gaps involving race and gender, and in the inner cities and outlying suburbs. In the Dallas school district, the African-American Success Initiative task force formed in September and is dedicated to improving the students’ academic performances.

Inside Ferguson’s classroom, some boys are wearing suit jackets, vests or ties. They’re required to dress up on meeting days. When they mumble, they’re firmly reminded by Ferguson to speak up and articulate.

At one point, he assigns them to write five things they hope to accomplish this year, and what’s hindering them. Some share that they want to pass the year, so they can move to the next grade.

“At the end of the day, you’ve got to be accountable,” Ferguson tells the group.

Then he asks the students to list 10 things that would make their mothers proud.

Strong influence

To the many boys here living with single mothers, Ferguson – who also is black – is one of the strongest male influences in their lives. He dedicates much of his time to the students, admittedly increasing stress on himself.

There’s frank talk about the presence of guns in the home and the importance of using birth control. The tone is conversational, with students often talking about challenges in their homes.

The students often meet for hours after school and volunteer with groups such as a homeless shelter on weekends. They work part-time jobs through the program.

But the challenge at hand is considerable. According to the Texas Education Agency, in 2010 the school was rated “academically unacceptable.” The school’s student body is about 81 percent black.

Zakari Smith, 17, is president of the group. He said he learned to cut people out of his life who were negative influences.

“I’ve gotten better in developing myself,” he said. “I used to go out and act stupid.”

Emanuel Foster, 18, admits he had behavior issues such as stealing.

“I feel like I’ve got a brotherhood now,” he said.

Planning ahead

Robert Edison, director of DISD’s social studies department and leader of the Dallas ISD task force, said the group is working on building more intervention and mentoring programs.

So far participants have reached out to black ministers. Edison understands that some question the reasoning of targeting such a specific group, but he said that it is necessary.

At one point, the task force convened a group of teen boys to speak out and to assess student attitudes.

“What stood out was that almost every one of those students said the one thing they needed was at least one person in their life who was a mentor,” he said. “And they admitted that some of them have a problem – that it’s not cool to be smart. So they have issues that are cultural in nature.”

The group’s next step will be establishing advocates at every campus to work with the students.

In a recent report, “A Call for Change,” the Council of the Great City Schools, a coalition of large urban districts, outlined how black boys lag the furthest academically compared with other groups, including black girls. The organization also found significant challenges among Hispanic males.

“It was a hard thing to come to grips with,” said Michael Casserly, executive director of the Washington-based organization. “In too many cases, our schools were doing little more than reflecting if not perpetuating many of the inequities in other sectors of society.”

Irving efforts

According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, black women are enrolling in Texas colleges and universities at much higher rates and have made “extraordinary progress.” About 7.8 percent of black women participated in the higher education system in 2009, about 3 percentage points higher than black male students.

Initiatives addressing the gaps aren’t limited to the inner city.

Educators in the Irving school district developed a program operating in several elementary schools known as Boys to Men. About 70 kids are involved, and the number of schools participating is still expanding.

Parent educator Maurice Walker, who is black, teaches small groups of boys character lessons either in the mornings or in the afternoon.

During a recent visit to a school, none of the 10 boys in the session said they had a man who lived at home. Many schools don’t have black male teachers. The children discuss goals. Walker, who said he was lucky to be raised close to his grandfather and stepfather, tries to stress to the students that becoming a professional athlete is not likely, despite the fact that he said at least 75 percent of the boys say that’s what they’d like to become. He carefully tracks their academic performances and behavior problems.

At the district’s Nimitz High School, a group of boys meet as part of “The Talented Tenth,” a reference to a W.E.B. Du Bois essay establishing the goal of having one out of 10 black Americans become college-educated leaders who work as professionals and inspire and lead positive change.

“It’s no secret in America that many of our boys unfortunately don’t have strong male role models that they can look toward living in their homes and giving them guidance,” Walker said. “That’s a very sad reality. Educators have realized that we can stand by and watch our boys fail or we can step up.”